Your basket is currently empty!

The undressed Gratteri: the allegory of bad government

Di Marco Fragale

“Gratteri! Chi non conosce storia e imprese

Di questo sfortunato Bel Paese?

Ma per tornarci su con la memoria,

non fa poi male riveder la Storia.

Storia verace di cervelli fini

di scrittori, poeti e scribacchini,

di dissacrate malelingue d’alto ingegno

e gente onesta del Pietroso Regno!

Signori, zotici ed alfieri,

questo è il miscuglio avito di Gratteri.

Albero di Scienza! nominato,

storico patrimonio del passato.

Fatti lontani di tant’anni fa

Al tempo di ricchezze e povertà.

Pagine d’una storia molto oscura,

sulla tragica fine di Monumenti e mura…”

(Pino Grisanti, versi inediti, anno 2001)

This is a story that has been hidden for centuries of a mysterious village in the Madonie called until a few centuries ago “Arvilu di la Scienza” (the tree of knowledge) – probably in relation to episodes that have their roots in a distant era – before that religious fanaticism and superstitious beliefs incited the people to rage on the most precious they had inherited from their own ancestors. We are talking about a shame that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the inhabitants of the village still carried with them, called by the neighboring communities “Crocifissori di Cristo” (Crucifiers of Christ) for having destroyed, at the end of the nineteenth century – under the advice of an enlightened prelate – the glorious castle of the Ventimiglia Lords and the walls of an ancient fortress to build a new Matrice. Pages of a very dark history until now sunk into oblivion. An ancient aphorism from Gratter reports:

“Gratteri: una calotta sferica, dove sputò il Diavolo e tutto inaridì!” (“Gratteri: a spherical cap, where the Devil spat and everything dried up!”.)

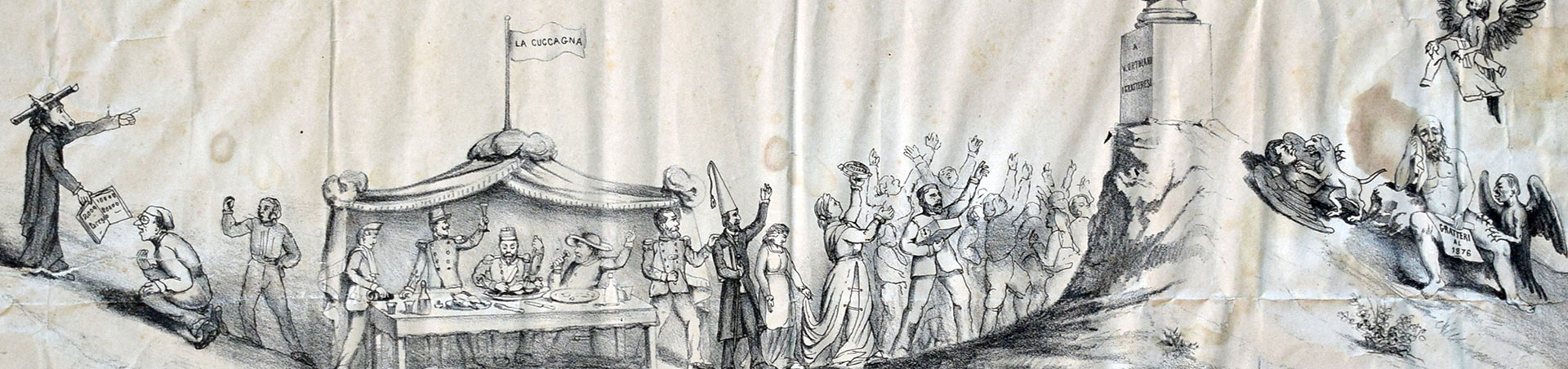

But let’s start from the beginning … A print from 1876 was recently found – in the house of a local scholar – which could be considered today a very important document, in an attempt to reconstruct a sad little-known page of local history in our century through the sources of the time. The print – entitled “Gratteri – L’inaugurazione del monumento al sindaco Notar Vincenzo Ortolano” – constitutes a sort of allegory of bad municipal government on the example of the one created in 1338 by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. In any case, from the writings that are reported on the paper, we know that this print was produced by the Lithography Visconti and Typography Oliveri in the year 1876. Above you can also read a wording by the same author:

“Io son coi buoni: non fo lega con gl’iniqui di qualunque colore essi siano, e il mio libero pensiero non renderò giammai schiavo dei voleri altrui”.

The image shows on the left, in an elevated position, a prelate represented with an equine head – allegorical criticism of the degeneration of the clergy – who, while with his left hand points a finger at a monument, with the other he holds an open book showing to an illiterate farmer who tries in vain, with lenses, to decipher its contents (2000 Paregio – 10000 20000).

At his side, another villain makes a sign to the religious that he has not fully understood his incitement and, to follow, a banquet presided over by civil and religious authorities – an allegory of greasy and dissolute life – who eat and toast together behind the fools citizens of Gratteri.

After that set table, a charlatan with a magician’s hat follows – an allegory of superstition and fanaticism – who, under the advice of an authority, incites a crowd of nobles and villains to cheer at the foot of a monument. The latter – built by the will of the Gratteresi – represents the marble bust of the Mayor, the living Vincenzo Ortolano (1829-1889), who is crowned by an angel with a wreath of brambles.

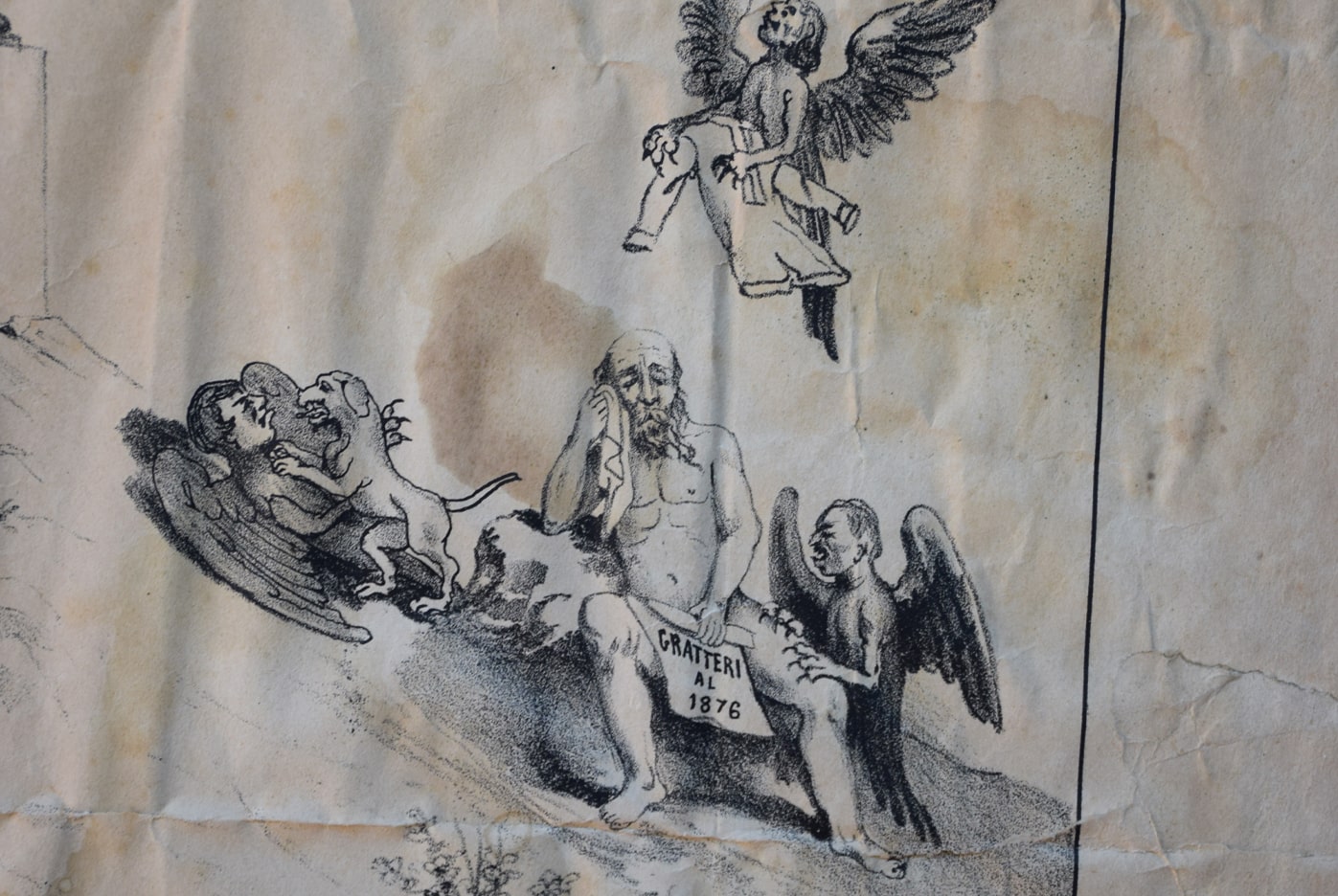

Behind the monument is the most pitiful image, that of three harpies attacking a poor naked and crying old man who wipes his tears with a handkerchief and carries a parchment with the inscription: “Gratteri al 1876” in his hand. This illustration is intended to represent the allegory of the Municipality of Gratteri stripped of all its possessions at the end of the 19th century, as can be read in the last vignette below: “Mi fecero angherie di nuova idea et diviserunt vestimenta mea”.

In fact, while one of the devils is bitten by a dog, the other ascends to heaven carrying the garment of the afflicted one, in turn scratched by the third winged devil. Under this scenario, a prelate is portrayed escorting a poor peasant carrying a sack of foreclosed grain on his shoulders.

Below, in the central part, another villain who, to let his cart pass, whips his horse so much as to destroy its walls. Finally, at the bottom left, seated on a ruin, a gentleman – presumably a landowner – who, with his maxims, wants to convince a naive populace to put fish in a basket to absolve him of an obligation.

The illustration is completed by some stanzas below regarding the “I detti dei personaggi” (sayings of the characters), which are listed below:

Campi: Narra la sacra e profana storia

Che i padri santi gli uomini preclari

Eran famosi per la pappatoria;

tutto finiva in cene e desinari!

Noi facciam buona tavola e buon viso,

E anderemo ridendo in Paradiso.

D’Amore: Di qui non tornano

Polli in cucina.

Servo: Nè le bottiglie

Nella cantina.

D’Amore: Animo amici

Sì, divorate,

Le nostre tasche

Sono impinguate:

E poi…il Sindaco,

Questi minchioni

Sanno provvederci

Di francesconi.

Guarino: Io chisto muorzo

M’agio a magnà,

Alla salute,

Di chillo minnà.

Torelli: Oh, sor dottore accetti un boccone.

Popolo: Osanna, osanna al padre della patria.

E. Dimarco: Gridate, non curate ai polmoni,

R. Lanza: Via, ti dò la metà a due tarì

Ma pensa a mandarmi i migliori…

Farace: Canaglia vi aggiusterò io; ho pieni

poteri e vi graverò di tante spese…

Villico: E la barracca cosi cammina

Sorte meschina, sorte meschina!

V. Bonafede: Venite signori, leggete e stupite;

questo è il bilancio e di qui a 20 anni,

grazie alla gran testa del nostro Sindaco

avremo il pareggio, ed in ciò un po’ di merito

l’ho anch’io.

Gratteri: Mi fecero angherie di nuova idea

“Et diviserunt vestimenta mea”.

In the first verse, the author uses a quote from the Italian poet Giuseppe Giusti who, in 1843, hurled himself with wit and satire of morality against “fasto ignorante di chi tiene tavola aperta, e la turpe servilità degli scrocconi” (G.Giusti, I brindisi – Versi editi e inediti, 1852).

The other lines reported are adapted to the scene and uttered by local characters or well-known authorities of the time who, with subtle sarcasm, mock the people of Gratteri, naively persuaded by the Mayor and the ecclesiastical authorities, to replenish the municipal coffers in order to equalize the balance sheet, in 20 years, with its own collection system.

To tell the truth, incidents of fraud such as these, by local administrations, were not entirely unusual in the southern post-Unification years.

From the investigation conducted in Sicily in 1876 by L. Franchetti and S. Sonnino we know that the central government was actually “powerless to know and suppress abuses in local administrations”.

In fact, even if the administration of the provincial and municipal councils was subjected to the supervision and protection of a prefect, this, in any case, had no other means of knowing what was happening in the individual municipalities, if not through the office papers and information from local authorities.

Often times he found himself in the dark, both for the flaws carried out under impeccable financial statements, and for the presentation by the municipal administrators of incomprehensible financial statements due to errors and confusion.

This was particularly the case in small municipalities where, very often, the feeling and knowledge of the law was lacking to such an extent that, in some municipalities, mayors have arbitrary arrests carried out for contravention of the laws on the ground tax or municipal councils impose on its own, a municipal ground tax (L.Franchetti e S.Sonnico, Relazioni economiche e amministrazioni locali in La Sicilia nel 1876, Vol. I Firenze 1877).

In fact, in the aftermath of the Unification of Italy, the South still presented a semi-feudal social structure, whose disastrous economic, social, political and moral consequences effectively prevented the formation of a modern and enlightened bourgeoisie.

Unofficially, the barons, the mayors, the prefects always held the power, money and social prestige. The population, lacking a real social and economic perspective, continued to be oppressed by the tax burden, despised, deprived of any right and excluded from political life.

On the other hand, when Sicilian laborers or miners found themselves, at the dawn of the day, in the town squares waiting to be chosen, by the gabelloti, for day labor in the countryside or in the mines, they were well aware that, in that feudal society, there was no possibility of defending one’s rights.

This state of profound backwardness, of course, could not have continued to be perpetrated except with the political support of the southern bosses and the local parliamentary class for the governments of the time which, from them, continued to draw lymph through patronage and corruption (Studi Storici Siciliani – Semestrale di ricerche storiche sulla Sicilia – Anno III, Fasc. III, Marzo 2016).

This also happened in Gratteri, a village with an agro-pastoral tradition, where the ruling class at that time was still the landowner who was considered I interpreter of the needs of the entire population, imposing taxes at will and seeking as justification to comply with the balance. By dusting off the registry archives of the Municipality of Gratteri, significant information regarding the local characters mentioned by the Author comes out:

Vincenzo Mario Ortolani (1829-1889), Notary, son of Don Domenico (Doctor of Law) and Donna Elisabetta Cipolla – was Mayor of Gratteri from 1871 to 1875. His house was located in Via San Leonardo and descended from a rich family of landowners (owners of the fiefdom of the common lands, Mancipa and Mannilo districts). His grandfather, Don Vincenzo Ortolani (1761-1827) – married to Donna Giuseppa Di Marco – and his uncle Giacinto Ortolani (1764-1846) were already Mayors of Gratteri in the 1920s.

Don Epifanio Di Marco (Notary, born in 1831, son of Don Enrico and Cirincione Donna Serafina) who worked as Mayor and Civil Status Officer of the Municipality of Gratteri from 1859 to 1862. His house was located in Corso Piazza (now Corso Umberto I).

Don Vincenzo Bonafede (Surveyor, born in 1824, son of m.stro Francesco and Bonafede Concetta) married to Donna Antonina Culotta. His house was located in Via Puzzarello.

Don Rosario Lanza (Owner, born in 1837, son of Antonio and Di Marco Rosolia) former Mayor of Gratteri from 1865 to 1866 and from 1879 to 1891. His house was located in a side street of Via Castellana, today Via Ruggieri, called in his honor Via Lanza / Salita Orto from the name of the family garden.

However, to fully understand the reasons that led a small Madonie village to be mentioned in the newspapers of the time, we should pause to reflect on some specific illustrations: the old man robbed of his possessions (allegory of the Municipality); the magician (allegory of superstition); the prelate with the horse’s head (allegory of the decay of the clergy).

These three figures would refer to a sad page of local history, that of the dispossession of the Municipality of Gratteri of the most significant monuments of the past and the destruction of the Castle. In 1811, the construction of a new Mother Church was started at the behest of the archpriest Paolo Lapi, designed to accommodate all the faithful of a community in strong population growth.

Thus, at the behest of the parish priest of the time, the ancient castle and part of the perimeter walls of the ancient stronghold were completely demolished with the inevitable destruction of the districts “di la Terra Vecchia”, “di la Porta Grandi” and “di Nostra Donna del Rosario”.

The grandiose construction was carried out with the contribution and the sweat of all the citizens, men and women, “viddani and galantuomini” who met every Sunday and transported the stone needed for the construction of the new matrix on mules. The construction site lasted about 30 years. The church was consecrated in 1854 to the Archangel Michael and officially completed in the year of grace 1900. Sad fate also fell to the Vecchia Matrice which was completely dismantled to translate the old altars and its values into the Nuova Matrice.

Here is what the Chaplet of the Holy Thorns reports, printed in 1918:

“La sontuosa custodia in marmo delle Sante Spine venne collocata nell’abside della principesca cappella dei Signori Ventimiglia dentro le mura del proprio castello, ora interamente distrutto e poi nella nostra antica Matrice. Da questa verso il 1873 venne tolta e collocata nella cappella della navata destra dell’attuale Matrice fondata nel 1811 per il grande zelo del Sac. Paolo Lapi, che poi fu il XII parroco di Gratteri” (Coroncina delle Sante Spine, anno 1918).

In fact, in addition to the ancient castle, the ruins of ancient churches such as that of Santa Maria del Rosario in castro were also used as building material, definitively abolished in 1818 (See Scelsi I., p. 77). Many of the works of art from various churches therefore merged into the Nuova Matrice which until 1855 was still without altars and brickwork (Ibidem).

In 2001, Pino Grisanti – a passionate researcher of local history – before dying, collected significant verses and ancient Gratteresi anecdotes that today, in the light of what is emerging, could add further pieces to those sad events that saw the protagonist “l’ arvilu di la scienza ”stripped of its fruits.

“Solo Gratteri solitario e affranto

Resta di questa terra un gran rimpianto,

per mano di eccelsi Cavalieri (Dell’Apocalisse)

che hanno fatto e disfatto qui a Gratteri,

tutto è stato sconvolto e sfigurato,

l’infelice storia e il suo passato”.

(Pino Grisanti, versi inediti, anno 2001)

Marco Fragale

(Università di Palermo)

Bibliografia:

Archivio di Stato di Palermo – Stato civile della Restaurazione – Gratteri.

Archivio anagrafico del Comune di Gratteri.

FALCONE FILIPPO, Il dibattito sul Mezzogiorno e il contributo dei siciliani alla Questione Meridionale in Studi Storici Siciliani – Semestrale di ricerche storiche sulla Sicilia – Anno III, Fasc. III, marzo 2016, Carocci Editore

FRANCHETTI LEOPOLDO, SIDNEY SONNINO, Relazioni economiche e amministrazioni locali in La Sicilia nel 1876, Vol. I Firenze 1877.

GIUSTI GIUSEPPE, I brindisi in Versi editi e inediti di Giuseppe Giusti, Firenze, Felice Le Monnier, 1852

Scelsi I. Gratteri. Storia, cultura e tradizioni, Palermo 1981 – rist. Cefalù, Tip. Valenziano, 2008.

SCILEPPI Don SANTO, “Cercherò le mie pecore e ne avrò cura”. Vita ecclesiale a Gratteri (PA) – Ed.Tip. Le Madonie, Castelbuono 2009.

SIRAGUSA MARIO, La borghesia nel cuore del latifondo siciliano tra XIX e XX secolo in Studi Storici Siciliani – Semestrale di ricerche storiche sulla Sicilia – Anno III, Fasc. III, marzo 2016, Carocci Editore